Breaking the Barriers to Justice for Widows

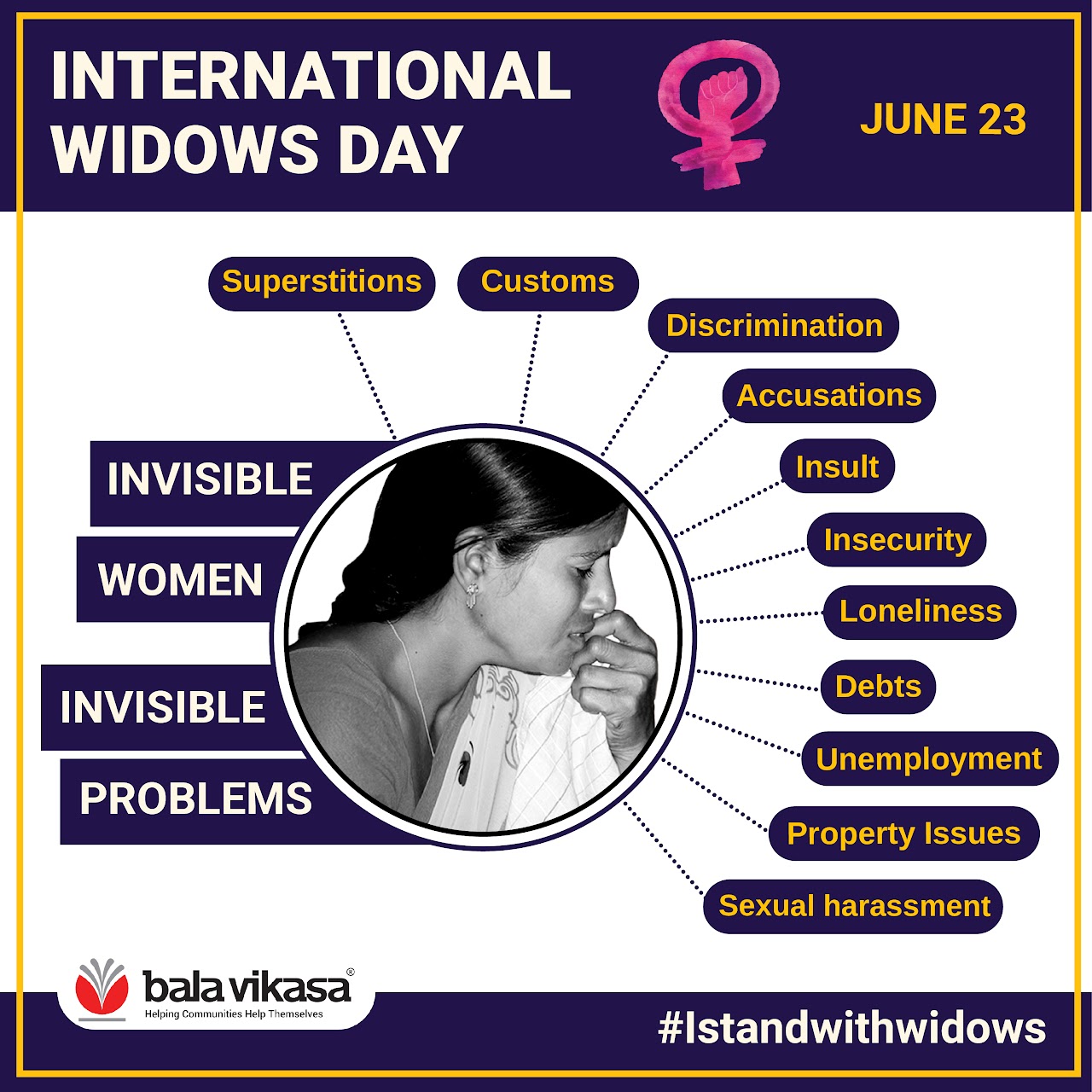

The life of a married Indian woman is often adorned with great reverence. Yet, when fate turns her into a widow, the contrast couldn't be starker. Exclusion, discrimination, shame, and injustice begin to invade her world, no matter her creed, location, education, or socio-economic status. Very few women are able to go about their lives unaffected by widowhood.

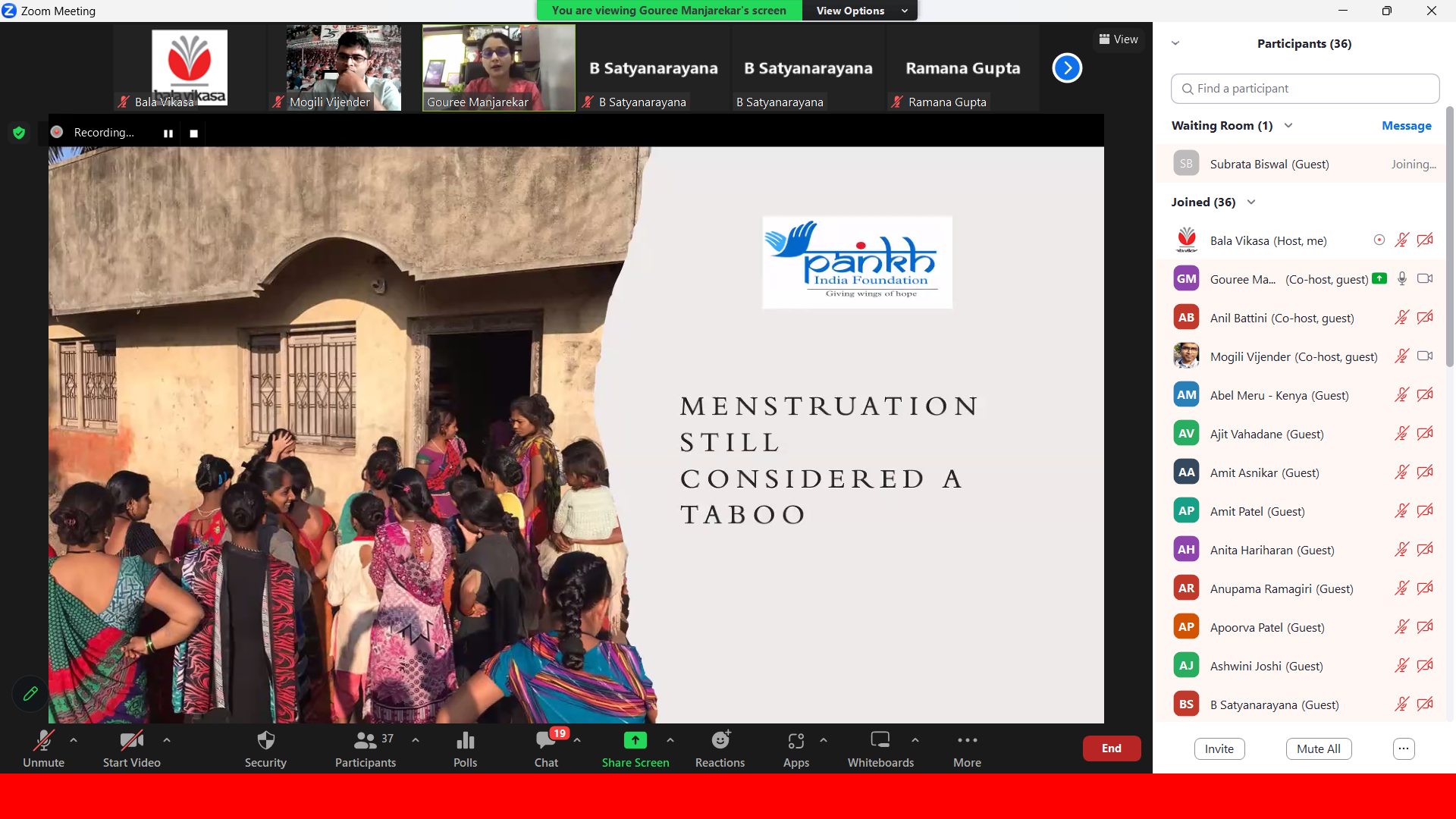

Social and gender norms still place an unreasonable burden on widows, none of which apply to men when they lose their wives. Worse still, these are perpetuated by their own family members, including women, under the weight of superstitious beliefs and customary practices. These compound the misery of widows already overwhelmed by the devastating loss of their life partner. And it doesn’t end here. Widowhood opens the gate for new challenges that threaten the very survival of these women and their children.

Upon marriage, many women come to stay with the husband at their in-law's place, as dictated by societal and cultural norms. They are expected to look after the health and well-being of their in-laws thereafter. Conversely, the wife’s needs are to be taken care of by the husband and the in-laws. These expectations remain more or less similar even in the case of working women, with some moderation. However, the idea that a daughter-in-law is not their own blood crops up suddenly upon the death of the husband leading to her being treated like a pariah in many families.

This leads many women to not only be denied emotional, moral, and financial support but also be meted out with unfair and discriminatory treatment. This could manifest in the form of a hostile environment at home, mistreatment and abuse, exclusion from decision-making processes, pressure to go back to their parent’s home along with the children, and denial of the husband’s share of the property. Some widows even report sexual abuse by some of the family members.

While there are laws enacted to help widows deal with some of these challenges, the process of seeking justice, even by legal means is not without challenge.

Take the case of Lakshmi (name changed) from Thorrur. Her in-laws asked her to contribute to the repayment of their house loan if she wishes to continue staying with them or find a rented place for herself. When she conceded to their demand, they changed the terms and said that they do not wish to accommodate any of their children or their families in their house going forward. When she pressed for her husband’s share of the property, she was told that she would get it only after their death. She now lives in a rented house in her in-laws’ village, hypervigilant and fearful of future attempts to deny her of her rightful share.

Jyothi (name changed) was widowed at the age of 21 with three children to look after. Her in-laws refused to give her any share in the property saying that they are not ready to write the title on her name (as guardian), in lieu of all her children being minors. They feared that as a young widow, she could always get remarried, in which case her second husband would also gain rights over it. This was not palatable to them. This, though, sheds light on another important issue - the perceptions and practicalities of widow remarriages.

Coming back to Jyothi, she took the help of a local lawyer to fight for her rights. Her lawyer informed her that their in-laws’ entire property was ‘sold’ to her two brothers-in-law and therefore she is not entitled to anything now. She claims to be duped by her own lawyer who worked against her interests for money. Well-wishers tell her that she can, still, put up a fight. She, however, does not possess the resources to do so, nor faith in the process.

These experiences highlight multiple issues. That of the judicial validity of different arguments put forward by families against widows, their unwitting acceptance in conformity to prevailing socio-cultural and gender norms, internalized fear complexes, lack of awareness and capital to access appropriate resources (social, intellectual, financial), unavailability of sound legal advice, gaps in provisions of law (that can be taken advantage of), very-real threats to their security, and by and large, a broken moral compass. These make it very difficult for widows to fight for their rights even when the letter of the law empowers them to do so.

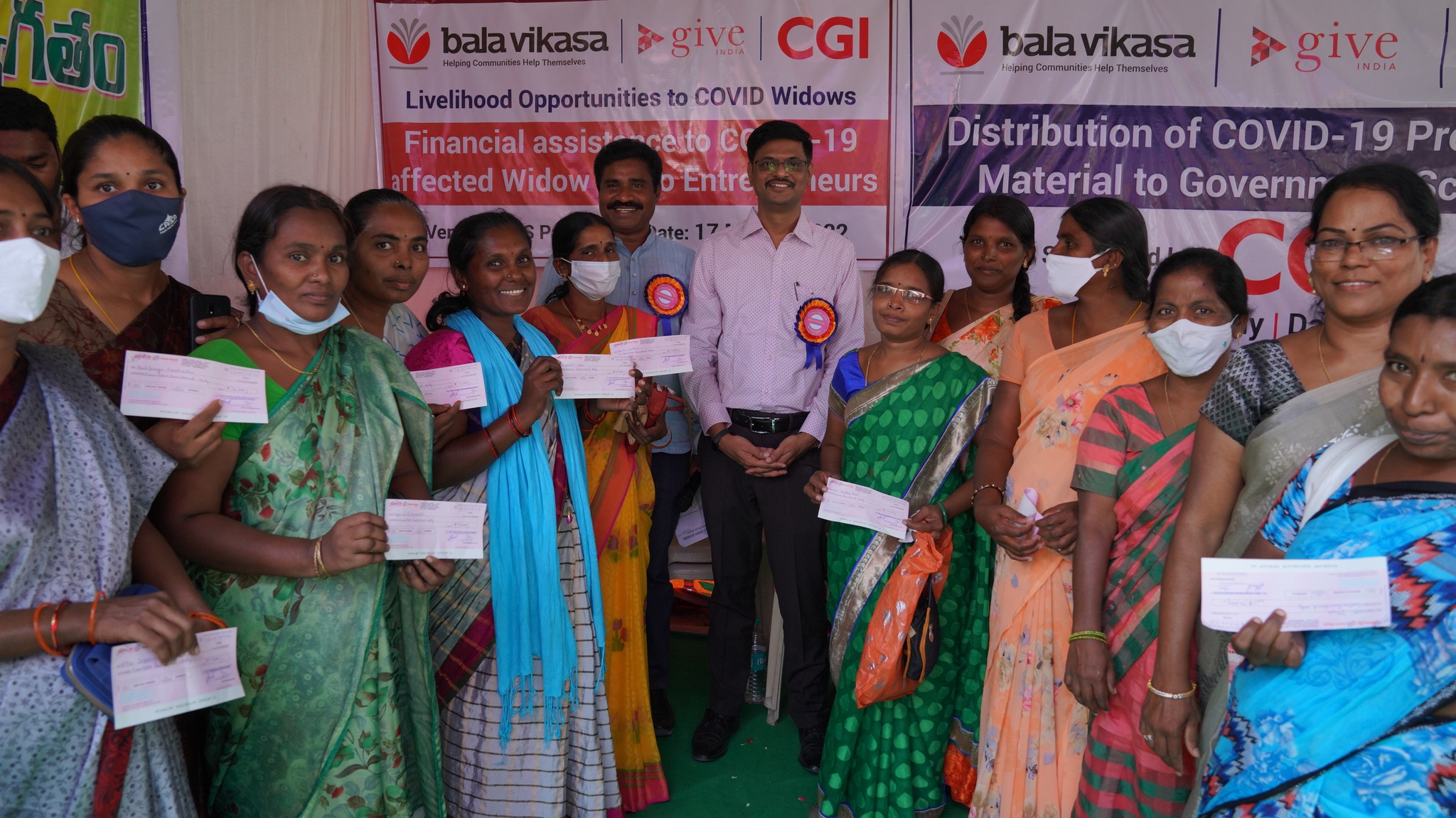

A lot of work needs to be done in this direction to help widows in realizing their full rights. Bala Vikasa has been advocating for a special ‘Prevention of Atrocities against Widows Act’ at a macro level to strengthen their cause. Setting up dedicated legal aid centers for widows at local courts is a suggestion that could be seriously explored. At a micro-level, awareness creation and education on widows’ rights is the need of the hour, especially for widows and various community workers. Different sections of civil society are to be actively engaged through workshops and seminars to onboard them as agents of change. All of these could move the needle a bit in the favor of widows.