Addressing Climate Change is Critical to Alleviating Poverty

Post the Covid-19 pandemic that ravaged global development indices, it’s not surprising to see experts across science, policy, and business, agreeing on what is increasingly becoming a globally-held worldview — delaying climate action is no longer an option.

In this respect, Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta’s remarks at UNEA couldn’t have been more opportune: “These increasing adverse weather and climatic occurrences sound a warning bell that calls on us to attend to the three planetary crises that threaten our collective future: the climate crisis, the biodiversity and nature crisis, and the pollution and waste crisis.”

UNEP’s report “Making Peace with Nature,” providing a comprehensive blueprint for these emergencies, couldn’t have come at a better time. With crippling climate disasters rising over the decades and emerging from the blow dealt by the COVID19 pandemic, nations are increasingly realizing that investing in solutions to address climate change and in green recovery is integral to developing and protecting communities, and ensuring sustainability.

For decades, however, climate change and poverty alleviation were considered disjointed issues

Most post-industrial economic growth has been based on unsustainable resource extraction and exploitation, making a few countries incredibly wealthy through unchecked emissions, without paying for the costs to the environment and human health. Ironically, these costs are being borne disproportionately by developing countries not even remotely connected to it. The high carbon lifestyle of developed nations has led to the excessive contribution of GHG emissions. The abnormal differences in per capita emissions of the US, Europe, India, and Africa bear witness to this.

A person in the wealthiest 1% leaves 175 times higher carbon footprint than one in the bottom 10%

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has long warned us that the planet’s temperature rose by 1.1°C on average since the 1880s and this minuscule rise is causing the spate of devastating floods and famines, the inundation of small islands, and colossal loss of human lives and natural capital, over the past two decades. Regardless of future emissions, we are already committed to further warming owing to our historical emissions. We are now headed for a 3.5°C warmer earth, and limiting the warming to 1.5°C isn’t an easy task as this demands Zero emissions by 2050.

In 2019, nearly 25 million people globally were displaced due to natural disasters and the number of people displaced within their own countries rose by almost 25%. The landmark ‘Kyoto protocol’ (1997–2012) failed to deliver because of the non-committal approach of signatory nations, besides the exclusion of some major emitters. Meanwhile, 25% of the Earth’s landmass experienced a shift in climate classification even as we still await a target-driven and legally binding climate action.

During the 2019 unprecedented flash floods in Hyderabad (India) 40,000 families were displaced, and USD 681 million worth of crops and property damaged. Last year, Australia lost 8.4 Million hectares of forest in one of the worst fires in history, while 1 Billion animals lost their lives in just 4 months due to extreme drought and fires.

Climate change inaction is causing the reversal of development

A fundamental climate change impact is ocean warming. Besides triggering extreme weather events, it’s also affecting the livelihoods of 650–800 million fishing communities. Adverse events would trigger harvest failure in multiple breadbasket locations globally and lead to rising food prices, particularly hurting 750 million people living below the international poverty line.

McKinsey estimates, by 2030, the average number of lost daylight working hours in India could increase to the point where between 2.5–4.5% of GDP could be at risk annually. In 2018, India lost USD 37 Billion due to extreme weather events.

For small island nations, the vulnerabilities are unthinkable. As sea levels rise from 26cm to 98cm by the end of the 21st century, it could trigger a mass exodus adding to the climate refugee issue. The poorest countries are more vulnerable to climate hazards as they rely more upon outdoors and natural capital and have less financial means to adapt quickly.

The world needs a stable and predictable climate for the smooth functioning of our lives and economies.

By 2050, 200 Million climate refugees will be driven out of the Middle East and South Asia alone (IEHS ). 70% of the worlds poor depend on natural resources for livelihood.

‘Climate Poverty’ and ‘Climate Refugees’, defining climate-induced poverty and loss of land, are increasingly being used to highlight the interconnection between climate change and poverty alleviation. We can’t solve poverty problems without addressing climate change simultaneously. Our window of opportunity for action is rapidly closing.

Climate change mitigation efforts aren’t enough. We need to heavily invest in climate adaptation as well.

Climate mitigation — a preventive proactive measure, and adaptation — a risk management reactive measure, are parallel, equal, and long-term actions. If mitigation seeks to prevent the environment from changing, adaptation seeks to help people live in a changing environment. Integrating mitigation and adaptation responses into development planning will inevitably reduce poverty, which will, in turn, better protect people against growing climate change challenges. Such measures include protecting people and assets, building resilience, reducing exposure, and ensuring that appropriate financing and insurance are in place.

Climate change impact is estimated to cost the global economy USD 7.9 Trillion. USD 1.8 Trillion in adaptation investments would prevent these costs entirely, as per GCA.

Countries can invest in reforestation and coastline restoration projects to improve water security, protect communities from natural disasters, and create economic opportunities. Just switching from fossil fuels to clean energy sources could add upwards of USD 26 Trillion to the global economy by 2030.

Ambitious climate mitigation is a must to limit long-term climate change impact and reduce risks.

We need to triple our efforts just to limit global warming to 2°C and increase our efforts fivefold to hold warming at 1.5°C. Renewable energy helps avoid GHG emissions, builds resilience to climate extremes, and creates new employment opportunities. Low-carbon mass transit systems (Metro or BRTS) could boost economic productivity by reducing traffic congestion and improving air quality. Solar photovoltaic and thermal systems avoid the usage of fossil fuels, improve indoor air quality, and prevent illnesses among women and children. Fiscal policy and carbon pricing can incentivize low-carbon investment and emissions mitigation, generate revenue to bolster social protection, support people in poverty, and help create good green jobs.

UN estimates developing countries need USD 70 Billion annually to adapt to climate change — as much as USD 300 Billion by 2030. 7,000 cities, 245 regions, and 6,000 companies have committed to mitigation, so far.

The 2015 Paris Agreement on Climate Change elevates multilateral institutions like the Green Climate Fund (GCF) that raise money to fund mitigation and adaptation projects in developing countries. If developed countries support the GCF, the Adaptation Fund, the Global Environment Facility, and the International Climate Initiative — it would help rapidly scale up efforts to tackle the climate crisis.

23 countries, which have decoupled economic growth from emissions through renewable energy, carbon pricing, and green subsidies and jobs, are reducing poverty faster than other countries — proving that the barriers are social and political, not technological or economic.

Climate advocates and activists, however, caution against climate apartheid.

554 companies committed to reductions in greenhouse gas emissions as a part of the “Science-Based Target initiative”, a voluntary self-reporting initiative, as of May 2019

An over-reliance on the private sector could lead to an inequitable situation where the wealthy pay to escape overheating, hunger and conflict, while the rest of the world suffers. Developing countries complain that there’s profound inequity in asking countries with low per capita emissions to bear the same burden as the high emitters — often developed nations.

Noted economists such as Raghuram Rajan recommend a per-ton carbon levy on nations emitting higher than the per capita average, which goes into the Global Carbon Reduction Incentive Fund that rewards low emitters, often the poorest and most endangered by climate change. Climate adaptation is ultimately about addressing social inequalities. Climate justice requires grassroots participation, as opposed to top-down implementation approach. Policies for adapting to climate change should build on the local and indigenous coping strategies.

Community-based approaches integrate adaptation strategies for poverty alleviation.

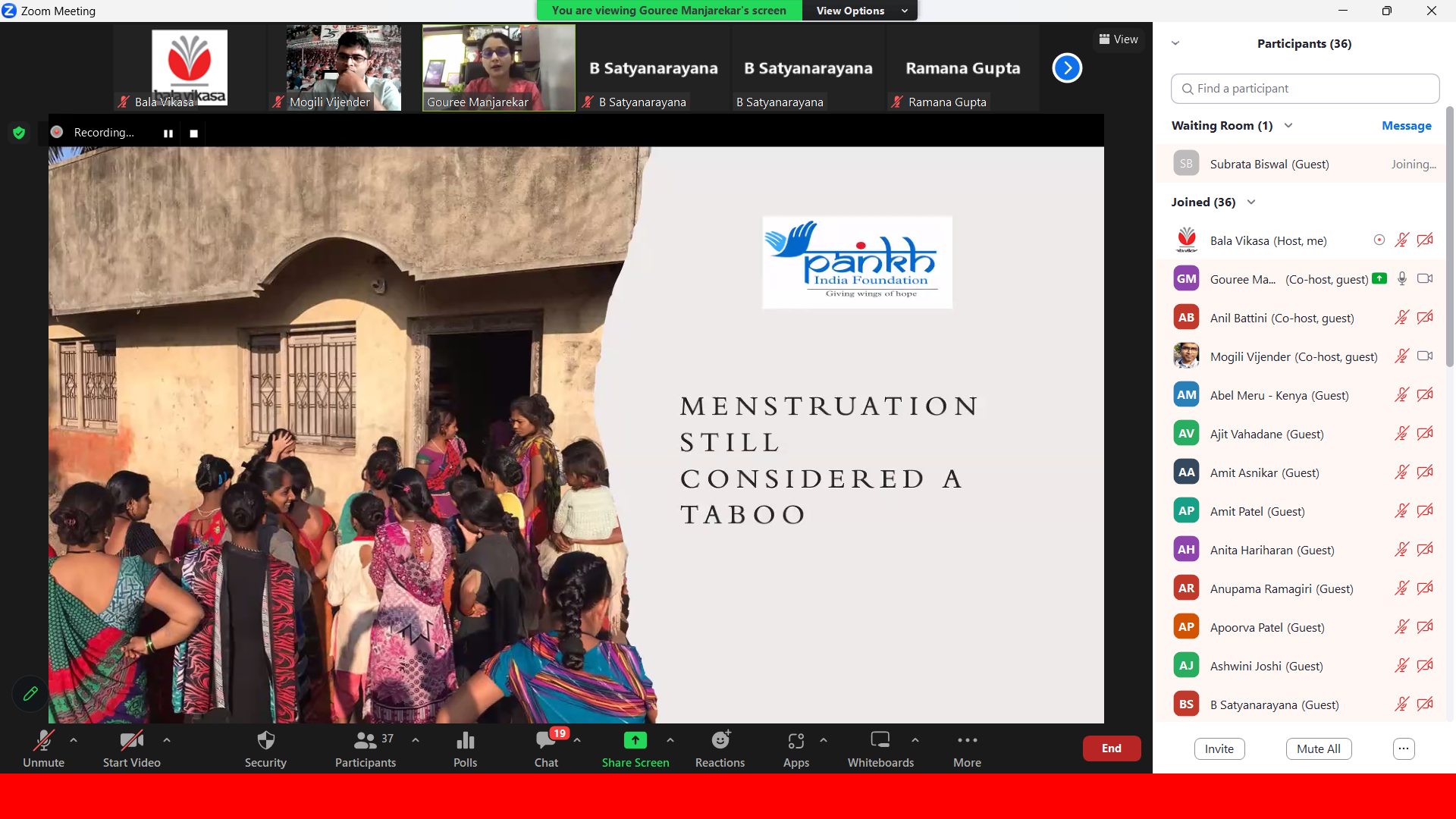

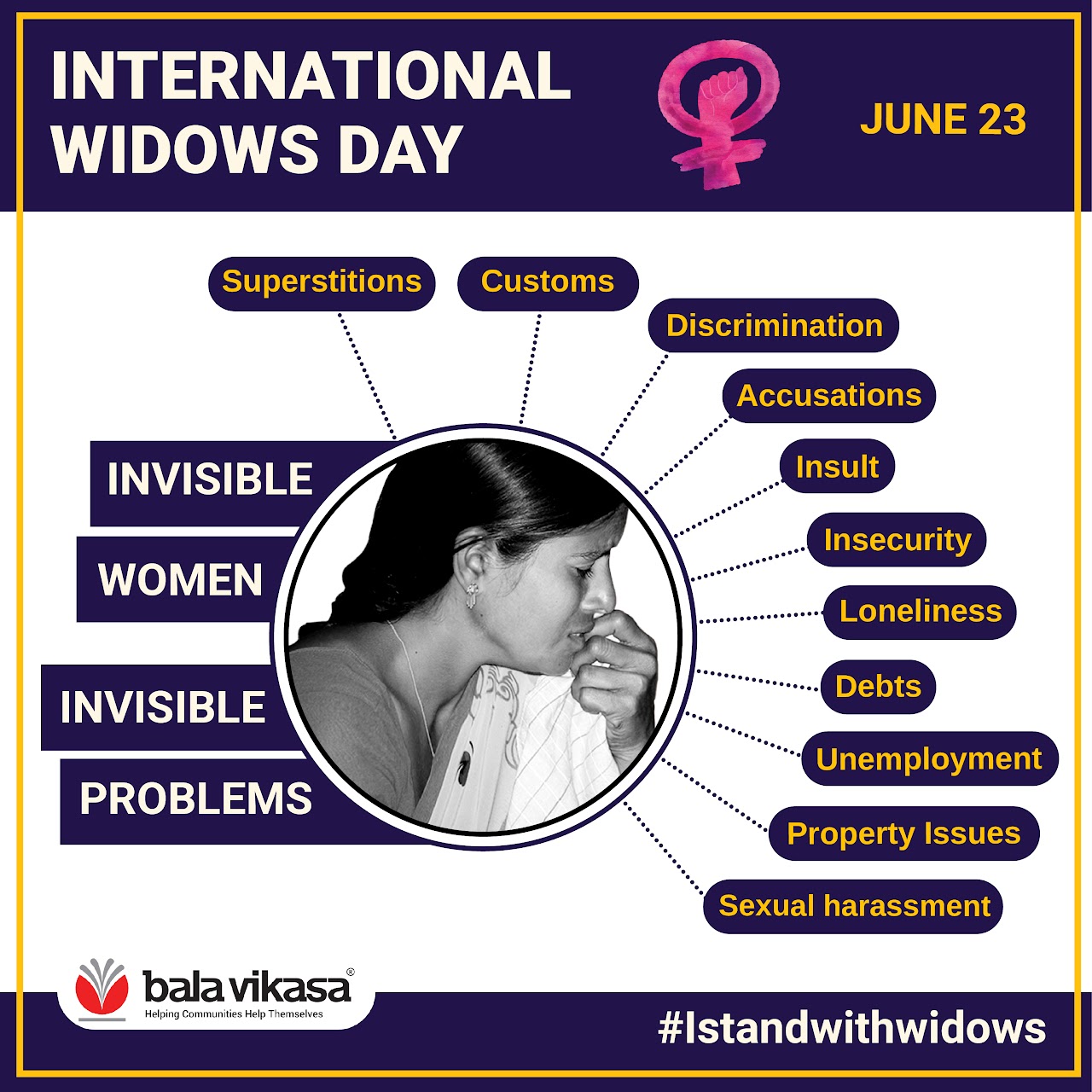

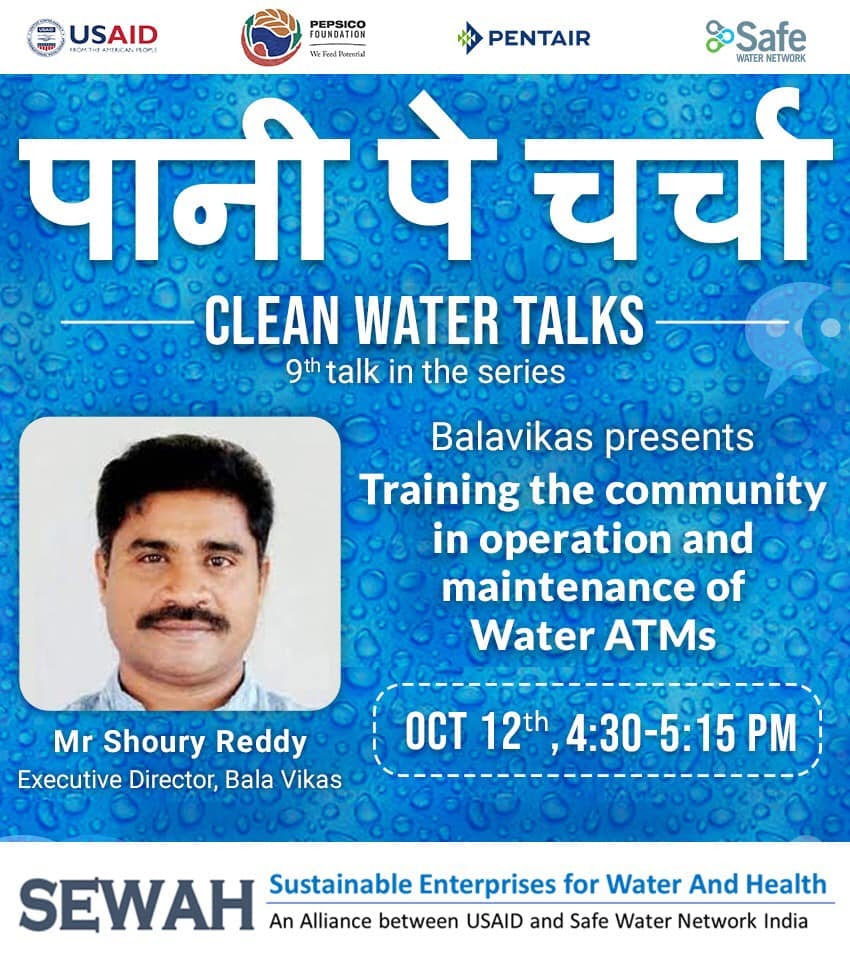

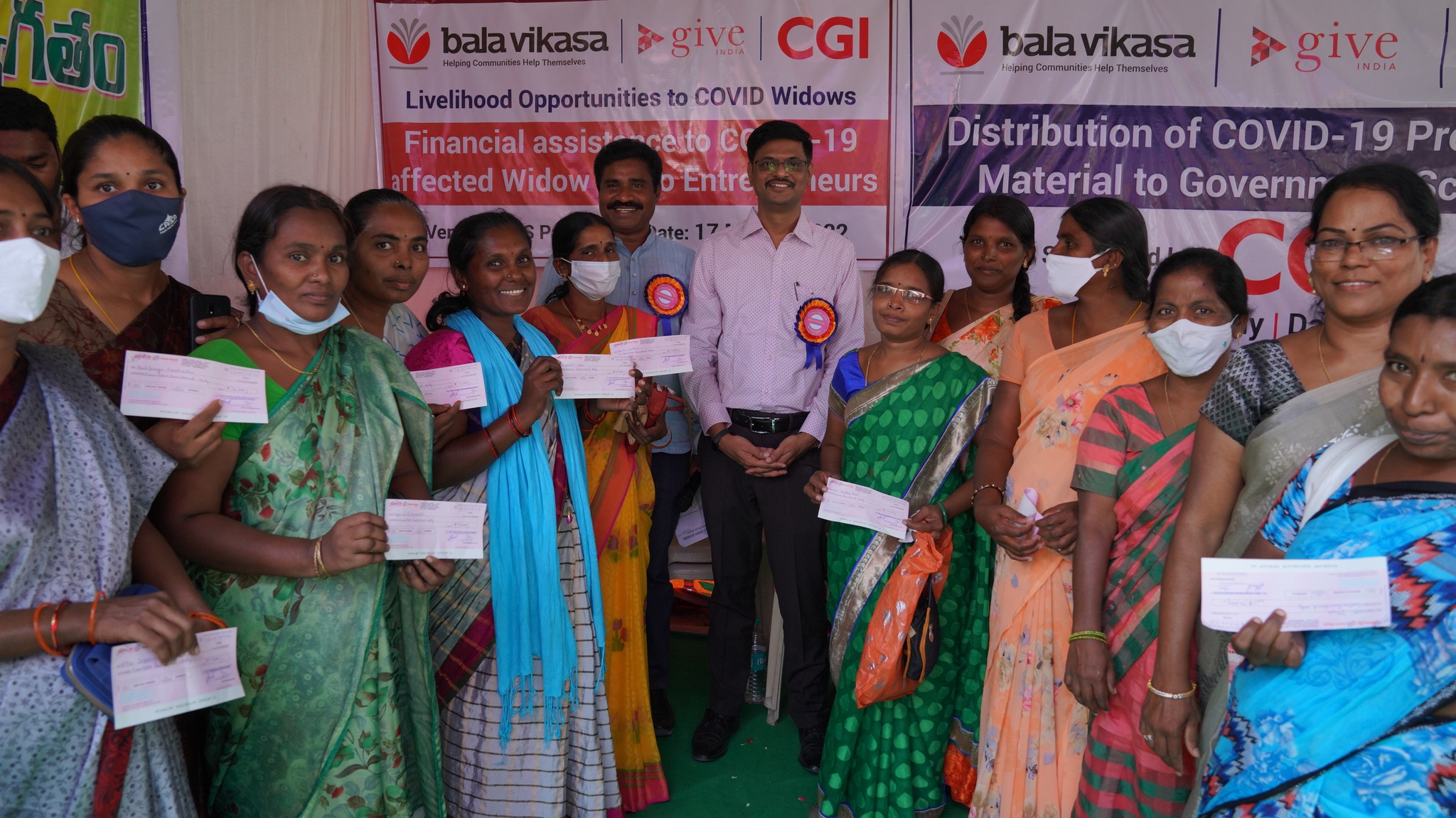

For civil society organizations such as Bala Vikasa, community adaptation and resilience measures are at the core of their operations. The organization has successfully implemented women and youth development programs, sustainable agriculture practices, lake restoration and water conservation interventions, tree plantation and safe water initiatives for millions of poor people.

It’s important that increased funding is available to such civil society organizations to focus on climate solutions. Fortunately, funding agencies are increasingly encouraging community-based solutions that successfully deliver a sustainable impact. For example, the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) and the UNDP are accelerating local action to build the resilience of the poor. Yet, the economic divide is rapidly widening. Economic growth, led by businesses, is the lifeline for any country. But, such growth needs to be inclusive and benefit the poor too.

The path to a safe, just and equal society isn’t very far with the support from responsible businesses

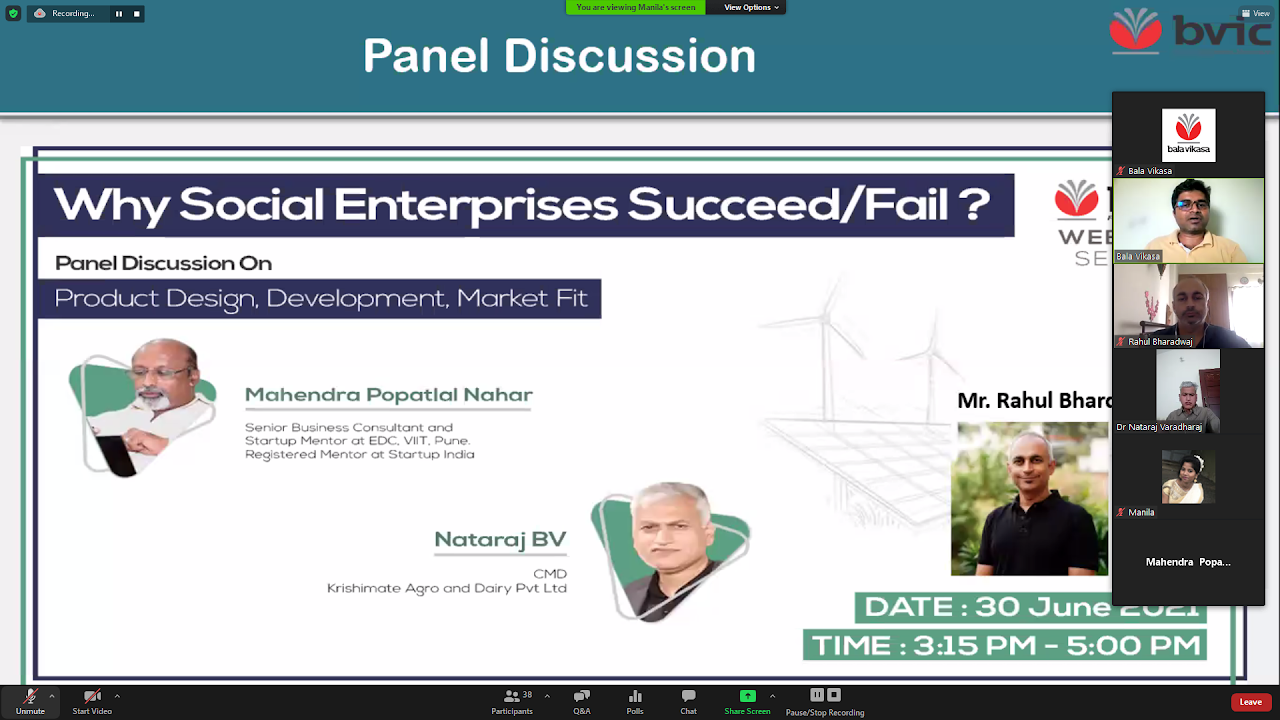

For businesses, disruptions are aplenty, and there’s no longer a ‘business as usual’ scenario. Adaptive business strategies and investments in low-carbon initiatives are integral to their survival and success. Bala Vikasa International Center (BVIC) has strongly advocated the integration of responsible practices in business strategies to help companies become more innovative, attractive, and sustainable. Businesses are increasingly adopting Environment, Social, and Governance (ESG) initiatives that also provide additional benefits — positive reputation, talent retention, competitive positioning, earning premium, reduced costs, and better risk management. Practices such as carbon neutrality, responsible consumption, green energy, afforestation, sustainable transport, circular economy, and triple bottom line approach are rapidly gaining momentum.

In the years ahead, countries will have to perfect the art and skill of climate adaptation.

It’s no longer viable to maintain current forms of infrastructure, agriculture, urban planning, land use, and economic development. Climate action calls for collective and collaborative efforts from all of us, to our fight against a gigantic problem that is challenging our very existence on this planet we call home.

“Adapting to climate change is a moral, economic, and environmental imperative .” Christina Chan, WRI

mate change is a moral, economic, and environmental imperative .” Christina Chan, WRI

" >

At the historic 5th UN Environment Assembly (UNEA), organized by the UNEP on 22nd and 23rd February, over 12,000 scientists, policymakers, and business leaders from around the world sought an urgent call for action to ensure that 2021 is the “turning point” for our planet in “green recovery that puts us on a pathway towards a low carbon, resilient and inclusive post-pandemic world.”

This comes barely months after global climate change advocates heaved a sigh of relief as US President Joe Biden recommitted his nation to the 2015 Paris Agreement on Climate Change — a serious climate action within hours of his inauguration in January.

Closer home, India too renewed commitment to climate action during the Climate Ambition Summit 2020 just last December, proudly announcing being on track to meet and exceed its Paris Agreement targets, besides pioneering the International Solar Alliance, and the Coalition for Disaster Resilient Infrastructure.

There is a growing agreement globally that delaying climate action is no longer an option.

Post the Covid-19 pandemic that ravaged global development indices, it’s not surprising to see experts across science, policy, and business, agreeing on what is increasingly becoming a globally-held worldview — delaying climate action is no longer an option.

In this respect, Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta’s remarks at UNEA couldn’t have been more opportune: “These increasing adverse weather and climatic occurrences sound a warning bell that calls on us to attend to the three planetary crises that threaten our collective future: the climate crisis, the biodiversity and nature crisis, and the pollution and waste crisis.”

UNEP’s report “Making Peace with Nature,” providing a comprehensive blueprint for these emergencies, couldn’t have come at a better time. With crippling climate disasters rising over the decades and emerging from the blow dealt by the COVID19 pandemic, nations are increasingly realizing that investing in solutions to address climate change and in green recovery is integral to developing and protecting communities, and ensuring sustainability.

For decades, however, climate change and poverty alleviation were considered disjointed issues

Most post-industrial economic growth has been based on unsustainable resource extraction and exploitation, making a few countries incredibly wealthy through unchecked emissions, without paying for the costs to the environment and human health. Ironically, these costs are being borne disproportionately by developing countries not even remotely connected to it. The high carbon lifestyle of developed nations has led to the excessive contribution of GHG emissions. The abnormal differences in per capita emissions of the US, Europe, India, and Africa bear witness to this.

A person in the wealthiest 1% leaves 175 times higher carbon footprint than one in the bottom 10%

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has long warned us that the planet’s temperature rose by 1.1°C on average since the 1880s and this minuscule rise is causing the spate of devastating floods and famines, the inundation of small islands, and colossal loss of human lives and natural capital, over the past two decades. Regardless of future emissions, we are already committed to further warming owing to our historical emissions. We are now headed for a 3.5°C warmer earth, and limiting the warming to 1.5°C isn’t an easy task as this demands Zero emissions by 2050.

In 2019, nearly 25 million people globally were displaced due to natural disasters and the number of people displaced within their own countries rose by almost 25%. The landmark ‘Kyoto protocol’ (1997–2012) failed to deliver because of the non-committal approach of signatory nations, besides the exclusion of some major emitters. Meanwhile, 25% of the Earth’s landmass experienced a shift in climate classification even as we still await a target-driven and legally binding climate action.

During the 2019 unprecedented flash floods in Hyderabad (India) 40,000 families were displaced, and USD 681 million worth of crops and property damaged. Last year, Australia lost 8.4 Million hectares of forest in one of the worst fires in history, while 1 Billion animals lost their lives in just 4 months due to extreme drought and fires.

Climate change inaction is causing the reversal of development

A fundamental climate change impact is ocean warming. Besides triggering extreme weather events, it’s also affecting the livelihoods of 650–800 million fishing communities. Adverse events would trigger harvest failure in multiple breadbasket locations globally and lead to rising food prices, particularly hurting 750 million people living below the international poverty line.

McKinsey estimates, by 2030, the average number of lost daylight working hours in India could increase to the point where between 2.5–4.5% of GDP could be at risk annually. In 2018, India lost USD 37 Billion due to extreme weather events.

For small island nations, the vulnerabilities are unthinkable. As sea levels rise from 26cm to 98cm by the end of the 21st century, it could trigger a mass exodus adding to the climate refugee issue. The poorest countries are more vulnerable to climate hazards as they rely more upon outdoors and natural capital and have less financial means to adapt quickly.

The world needs a stable and predictable climate for the smooth functioning of our lives and economies.

By 2050, 200 Million climate refugees will be driven out of the Middle East and South Asia alone (IEHS ). 70% of the worlds poor depend on natural resources for livelihood.

‘Climate Poverty’ and ‘Climate Refugees’, defining climate-induced poverty and loss of land, are increasingly being used to highlight the interconnection between climate change and poverty alleviation. We can’t solve poverty problems without addressing climate change simultaneously. Our window of opportunity for action is rapidly closing.

Climate change mitigation efforts aren’t enough. We need to heavily invest in climate adaptation as well.

Climate mitigation — a preventive proactive measure, and adaptation — a risk management reactive measure, are parallel, equal, and long-term actions. If mitigation seeks to prevent the environment from changing, adaptation seeks to help people live in a changing environment. Integrating mitigation and adaptation responses into development planning will inevitably reduce poverty, which will, in turn, better protect people against growing climate change challenges. Such measures include protecting people and assets, building resilience, reducing exposure, and ensuring that appropriate financing and insurance are in place.

Climate change impact is estimated to cost the global economy USD 7.9 Trillion. USD 1.8 Trillion in adaptation investments would prevent these costs entirely, as per GCA.

Countries can invest in reforestation and coastline restoration projects to improve water security, protect communities from natural disasters, and create economic opportunities. Just switching from fossil fuels to clean energy sources could add upwards of USD 26 Trillion to the global economy by 2030.

Ambitious climate mitigation is a must to limit long-term climate change impact and reduce risks.

We need to triple our efforts just to limit global warming to 2°C and increase our efforts fivefold to hold warming at 1.5°C. Renewable energy helps avoid GHG emissions, builds resilience to climate extremes, and creates new employment opportunities. Low-carbon mass transit systems (Metro or BRTS) could boost economic productivity by reducing traffic congestion and improving air quality. Solar photovoltaic and thermal systems avoid the usage of fossil fuels, improve indoor air quality, and prevent illnesses among women and children. Fiscal policy and carbon pricing can incentivize low-carbon investment and emissions mitigation, generate revenue to bolster social protection, support people in poverty, and help create good green jobs.

UN estimates developing countries need USD 70 Billion annually to adapt to climate change — as much as USD 300 Billion by 2030. 7,000 cities, 245 regions, and 6,000 companies have committed to mitigation, so far.

The 2015 Paris Agreement on Climate Change elevates multilateral institutions like the Green Climate Fund (GCF) that raise money to fund mitigation and adaptation projects in developing countries. If developed countries support the GCF, the Adaptation Fund, the Global Environment Facility, and the International Climate Initiative — it would help rapidly scale up efforts to tackle the climate crisis.

23 countries, which have decoupled economic growth from emissions through renewable energy, carbon pricing, and green subsidies and jobs, are reducing poverty faster than other countries — proving that the barriers are social and political, not technological or economic.

Climate advocates and activists, however, caution against climate apartheid.

554 companies committed to reductions in greenhouse gas emissions as a part of the “Science-Based Target initiative”, a voluntary self-reporting initiative, as of May 2019

An overreliance on the private sector could lead to an inequitable situation where the wealthy pay to escape overheating, hunger and conflict, while the rest of the world suffers. Developing countries complain that there’s profound inequity in asking countries with low per capita emissions to bear the same burden as the high emitters — often developed nations.

Noted economists such as Raghuram Rajan recommend a per-ton carbon levy on nations emitting higher than the per capita average, which goes into the Global Carbon Reduction Incentive Fund that rewards low emitters, often the poorest and most endangered by climate change. Climate adaptation is ultimately about addressing social inequalities. Climate justice requires grassroots participation, as opposed to top-down implementation approach. Policies for adapting to climate change should build on the local and indigenous coping strategies.

Community-based approaches integrate adaptation strategies for poverty alleviation.

For civil society organizations such as Bala Vikasa, community adaptation and resilience measures are at the core of their operations. The organization has successfully implemented women and youth development programs, sustainable agriculture practices, lake restoration and water conservation interventions, tree plantation and safe water initiatives for millions of poor people.

It’s important that increased funding is available to such civil society organizations to focus on climate solutions. Fortunately, funding agencies are increasingly encouraging community-based solutions that successfully deliver a sustainable impact. For example, the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) and the UNDP are accelerating local action to build the resilience of the poor. Yet, the economic divide is rapidly widening. Economic growth, led by businesses, is the lifeline for any country. But, such growth needs to be inclusive and benefit the poor too.

The path to a safe, just and equal society isn’t very far with the support from responsible businesses

For businesses, disruptions are aplenty, and there’s no longer a ‘business as usual’ scenario. Adaptive business strategies and investments in low-carbon initiatives are integral to their survival and success. Bala Vikasa International Center (BVIC) has strongly advocated the integration of responsible practices in business strategies to help companies become more innovative, attractive, and sustainable. Businesses are increasingly adopting Environment, Social, and Governance (ESG) initiatives that also provide additional benefits — positive reputation, talent retention, competitive positioning, earning premium, reduced costs, and better risk management. Practices such as carbon neutrality, responsible consumption, green energy, afforestation, sustainable transport, circular economy, and triple bottom line approach are rapidly gaining momentum.

In the years ahead, countries will have to perfect the art and skill of climate adaptation.

It’s no longer viable to maintain current forms of infrastructure, agriculture, urban planning, land use, and economic development. Climate action calls for collective and collaborative efforts from all of us, to our fight against a gigantic problem that is challenging our very existence on this planet we call home.

“Adapting to climate change is a moral, economic, and environmental imperative .” Christina Chan, WRI

mate change is a moral, economic, and environmental imperative .” Christina Chan, WRI